****************************

This page and its contents, including photographs is Copyright To Anne Frandi-Coory All Rights Reserved 13 July 2015

…..

I bought this book to help with my research into the origins of our Italian ancestors’ surnames.

Our Italian Surnames by Dr Joseph G. Fucilla was originally published in 1949 and is still widely regarded as the definitive book on Italian Surnames. Professor Fucilla, who earned a doctorate in Romance Languages (University of Chicago 1928), has written hundreds of articles and numerous books on Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese linguistics. Onomatology, the study of the origin and history of proper names and another facet of Dr Fucilla’s vast erudition, was the field out of which emerged Our Italian Surnames.

The information contained in this wonderful book is vast. Many names are derived from animals, occupations, geography, birds, botanica, music and the arts. For the purposes of this post, I am concentrating on the origins of the names Frandi and Greco (later Anglicised to Grego).

****

********

The Evolution of Italian Surnames

Dr Fucilla writes: A surname or family name may be defined as an identification tag which has legal status and is transmitted by the male members of a family from generation to generation. It is a comparatively recent phenomenon. It is in Italy perhaps more than any other nation that a person may be identified as a native of a definite section of the country or even of a particular province through his given name.

Among the Hebrews, only one name used to be employed, but during the Greek and Roman dominations a second temporary name was adopted for individuals, such as Paul of Tarsus, Mary Magdalen (from Magdala). Christianity with its institution of a single baptismal name and the one-name system of the Germanic tribes who were soon to become the masters of Europe, eventually caused the collapse of the whole Roman name system.

What causes names to be changed over time? Dr Fucilla posits that: These changes can be explained under six headings….

translations, dropping of final vowels, analogical changes, French influences, decompounded and other clipped forms, and phonetic re-spellings. By means of these it will be possible to explain the vast majority of those Italian surnames which we find in Anglicised form.

*********

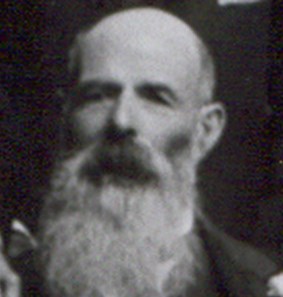

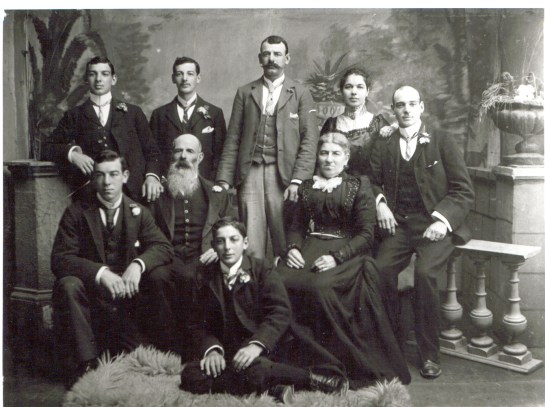

Aristodemo Giovanni Frandi was born in Pistoia in Tuscany in 1833. The original ‘Aristodemos’ is a Greco/Roman name. However, the only city in Italy I visited where there were people still living with the name Frandi was in Pisa, where two of Aristodemo’s children, Ateo and Italia were born. The two men I traced worked for local government in Pisa.

The only historical name I could find that came even close to Frandi is Ferrandy or Ferrandi, which is very common in Italy, especially in the north. However, it does suggest Gallic origins and as was frequent in ancient times, Ferrandy/Ferrandi slowly became Frandi to fit in with other simplified Italian spellings which often end in ‘I’. When speaking to native Italians, they pronounce Frandi as Ferrrrrandi anyway, rolling their rrrs. Conversely, Ferrandi is a very common name in France!

Dr Fucilla studies add more weight to my view that the name Frandi/Ferrandy is a French derivative. In his chapter headed Topographical Names, he writes:

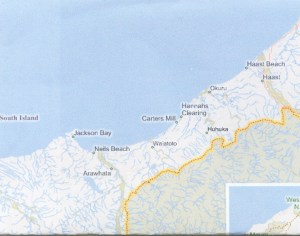

We may divide the natural and artificial topographical features that have given rise to Italian surnames ….. among them he lists several mineralogical and agrarian characteristics such as the prefix ferro which is the one we are interested in. This refers to iron (ore) generally but in the agrarian sense it refers specifically to the land and its minerals. We know that as a young man Aristodemo worked on the land as did most of his countrymen. When Aristodemo decided to emigrate with his family to New Zealand in 1875, the very real draw card was the allocation of 10 acres of free land on the West Coast. And later when the family settled in Wellington, their dream was to own a farm, which was eventually fulfilled.

In another chapter under the heading Geographical Names, which are frequently used in Italian surnames, Dr Fucilla documents the French/Italian name La Fiandra which means ‘from Flanders’ which in parts of its history was ruled by the French. Italians with French connections added ‘La’ to their surnames. Aristodemo called his first born son, Francesco, a derivative of France. It is possible that Frandi is a compound name of both La Fiandra and Ferrandy/Ferrandi. Dr Fucillo devotes a chapter to such compound names in which place names, nouns, occupations, religious references, and others, were compounded into abbreviated form.

In the mid 19th Century, when Aristodemo was in his 20s, all young men were conscripted into the regular army to protect territory in Northern Italy held at various times in more recent history by the Austrians, Germans, and the French. Most of the men were agricultural workers, and their loss was keenly felt by their families who needed them to tend the land.

Here are excerpts from my book ‘Whatever Happened To Ishtar?’ pages 286-287:

Aristodemo was conscripted into the regular army in 1859, 1865-1866 against the Austrians, at Ancona, a major port city at the base of the Apennines in the Marche region of the strategic East Coast of Italy which faced the Adriatic Sea. Then at Tirolo which is a tiny commune in the province of Bolzano-Bozen in the Italian region of Trentino-Alto-Adige in the far north of Italy, between Austria and Switzerland.

Aristodemo returned to Pisa to prepare for his marriage to Annunziata Gustina Fabbrucci in 1863. A year later the couple travelled north where Aristodemo was barracked with the regular army while Annunziata lived a few miles away in an Italian conclave. It was during this conscription period that Annunziata gave birth to their first child Francesco, in 1866 at Lake Lugano. Eventually, Aristodemo left the armed forces and worked for the fledgling Italian railways laying tracks, the best chance for work in an Italy in the throes of the industrial revolution and the confiscation of farmlands, which threw Italy into a new kind of poverty.

I have discounted Frandi as being derived from any form of the occupational prefix Ferra in its relationship to Ferrari, metal worker, or Ferroviere, railway worker, as a surname. The use of Ferroviere as a surname is very rare and its use is a very recent phenomenon.

Interestingly, Aristodemo’s mother was named Caterina Degli Innocenti Cashelli …Italians often used their parents’ names, or other family names, as middle names depending on where they come in the family hierarchy eg firstborn etc. Degli Innocenti is not a family name. It is the name given to all babies who are orphaned or abandoned and who are placed as foundlings in convents or ‘foundling hospitals’ (Hospital of the Innocents) . On one of our visits to Florence we came upon a beautiful building with coloured tiles depicting religious themes embedded above the doorway. Also written on the tiles were the words ‘Ospedale Degli Innocenti’ and when I inquired as to what the purpose of the hospital was, this was the explanation...a foundling hospital or sanctuary. Children were only baptised with this name if they were foundlings. The origins of Caterina’s given surname, Cashelli, are unclear, but it is possibly related to casella or caselli meaning dairy.

In 1928 a law was passed in Italy forbidding the imposition upon foundlings or illegitimates of names and surnames that might cast reflection on their origin. The law has probably stopped the increase of such names, but has hardly affected those already in existence. Ripples in a pond: this sort of stigma can and did affect the fortunes of those so named.

Pistoia is an ancient city with remnants of Gallic, Ligurian and Etruscan settlements everywhere. It is possible to trace the origins of Pistoia back to the 2nd Century BC when the Romans established a settlement there for the provision of its militia during the wars against the Ligurians. The Oppidum Romano (fortified citadel) achieved a certain importance in the 4th Century AD and its growth was favoured by its position along the Via Cassia the road that connected Rome to Florence and Lucca. The origin of the name Pistoia is possibly Pistoria Roman for bread oven. Roman troops were garrisoned and replenished there.

******

Filippo Greco was born in 1869 in Amalfi, Italy. Amalfi had close connections with Gaeta, a Greek trading port, and Gaetano and Gaetana were Greco male and female family names respectively, so it’s more than likely Filippo’s extended family originated there. Gaeta has fortifications which date back to Roman times and these fortifications were extended and strengthened in the 15th century, especially throughout the history of the Kingdom of Naples (later the Two Sicilies). There is evidence that Filippo’s early ancestors came from original Greek settlements in Sicily.

Grego is the anglicised version of Greco, which was originally a name given to those living in Greek settlements in Southern Italy. Since the days of the Romans, Greco has been a synonym of astuteness and disloyalty and often connotes a stammerer. Dr Fucilla suggests that some names such as Greco, have acquired a depreciative, figurative meaning which may now and then have led to their application to native Italians.

To summarise Dr Fucilla’s conclusions:

Anglicisation of Italian surnames is achieved by the drive of two strong forces converging upon their goal from opposite directions. One force, the most powerful of the two, represents non Italians who consciously or unconsciously in speech or in writing, make Italian names conform to English linguistic patterns, spelling, or individual names or types of names with which they happen to be acquainted. The other force represents the people of Italian origin who deliberately change their names or tolerate modifications made by outsiders as a concession to their new environment.

Finally, a very interesting paragraph from Dr Fucilla’s book:

Greek, Roman, Germanic and Hebrew Patronymical Names.

About 650 BC Ligurians, Illyrians, Umbrians, Etruscans, Sabini, Latini, Greeks, and Carthaginians occupied the various parts of Italy. They were all sooner or later, assimilated by Rome. After the fall of the Roman Empire a number of Germanic peoples including the Lombards, Franks and Normans, overran the peninsula. They too, were assimilated by their environment and with the others, through centuries of cross breeding fused into a fairly close-knit ethnical group now called the Italians. Yet despite fusion, traces still remain particularly in the guise of place names that carry us back to one or another of the stocks just mentioned. However, from the standpoint of personal surnames, a virtual monopoly is enjoyed only by three of the groups: Greeks, Romans and Germans. Their names eventually spread all over the country and from time to time through invasion, immigration, cultural tradition and religion, received reinforcements and accretions. A large mass of personal surnames was later adopted from an outside group, the Hebrews.

See here: Mansi; My Fascination With Italian Surnames Part 1

For more information about my book,

Whatever Happened To Ishtar? – A Passionate Quest to Find Answers for Generations of Defeated Mothers and to purchase a copy HERE is the link: https://frandi.wordpress.com/2010/04/15/publicaton-of-whatever-happened-to-ishtar/