This page, including images and text, is Copyright To Anne Frandi-Coory All Rights Reserved 27 November 2015

Update 7 June 2017:

This morning I received this email from Sister Joanna …and for some reason, it brought tears to my eyes:

Hello Anne,

My niece sent me your story on Facebook yesterday and I well remember our serendipity meeting.

I gather you are a writer in your own right…. Well done.

I am now a very old nun on a walker, going blind and hearing is much to be desired.

Blessings on your continuing search,

Regards

Sr Joanna (Maurya Laverty) Dn

*************************************************************************************

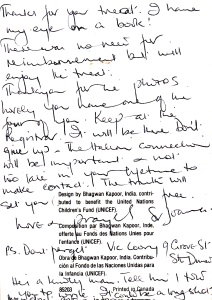

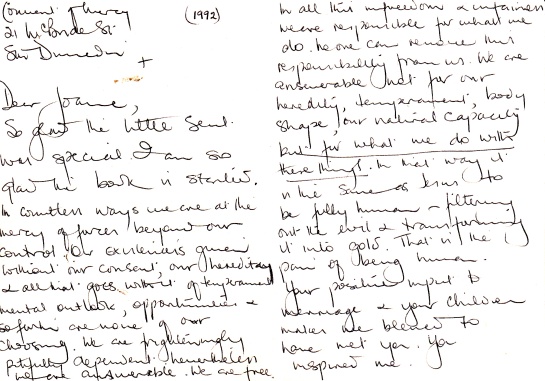

A Card – From Sister Joanna 1992

Excerpt from Whatever Happened To Ishtar?; A Passionate Quest To Find Answers For Generations of Defeated Mothers

**************************************

A CARD – from Sister Joanna “this image of Virgin Mary was a favourite kept by your ‘foster mother’ Sister Christopher.”

*****

[Note from author: My mother named me ‘Anne’ at birth, after her youngest sister, but it was changed to Jo-Anne by my Lebanese extended family when I was in my early teens because there were already “too many Annes in the family”, and because my father’s name was Joseph…you see?]

*****

Dear Anne

In countless ways we are at the mercy of forces beyond our control, our existences given without our consent; our heredity and all that goes with it of temperament, mental outlook, opportunities and so forth are none of our choosing. We are frighteningly, pitifully dependent. Nevertheless we are answerable. We are free. In all this freedom and unfairness we are responsible for what we do. No-one can remove this responsibility from us. We are answerable not for our heredity, temperament or our natural capacity, but for what we do with these things…Your positive input to your children makes me blessed to have met you. You inspire me. Don’t give up…the Italian connection will be important and not too late in your lifetime to make contact. The truth will set you free.

Love and prayers

Sister Joanna (Maurya Laverty) 1992

*************************************

Rear view of St Philomena’s (image: AFCoory)

Dunedin, New Zealand 1992

The Mercy Orphanage for the Poor had to be my first port of call. So Paul, my daughter Gina and I set off from Blenheim to Dunedin on a mission to connect the dots that made up my early years. During the eight hour drive to Dunedin, my feelings were mixed. I was deeply anxious about facing nuns again. I always held them in awe, afraid of them in a superstitious way, much as one is afraid of the power of an omnipresent god. We pulled up outside the 1.9 metre high concrete walls of the Roman Catholic orphanage in Adelaide Street, Dunedin. It was as if, by fencing off this relic from the past, the Catholic hierarchy could pretend it wasn’t there. It was right next door to the auspicious St Patrick’s Basilica, an incongruous sight.

As I peered over the top of the wall, I was at first struck by how small the yards and buildings appeared. An analogy of an abandoned movie set sprang to mind as I surveyed the scene below me. I turned and glanced at Paul and Gina, sitting in the car smiling at me and gesturing for me to go in. As usual they intuited that this was something I needed to do alone, so I went around the side of the fence and in through a slightly ajar, dilapidated gate.

It was a strange feeling, going back there all these years later. My heart pounded wildly, seemingly out of any rhythm, and I felt hot even though it was a chilly Dunedin day. The first building I came across was the drab concrete steep-roofed, edifice that was St Philomena’s Dormitory. ‘Charles Dickens!’ I thought. Rust stains streaked down from the eroding exterior fire escape. Windows always played a significant part in my memories and I immediately recognised those tall, narrow sashes. But I just couldn’t reconcile in my mind how small that building was now, compared to my memories of it. When I used to run in and out of the dormitory, it seemed a massive structure, housing dozens of ‘big’ girls in school uniform and ubiquitous nuns in black and white habits. It was I remembered, a dormitory for older girls, mostly boarders, when I had been there.

I was deep in my thoughts when I spied a small nun dressed in a knee-length black habit, with a white-trimmed black headscarf partially covering her hair. Her modern but matronly mode of dress was not that of the nuns present during my incarceration there, that was for sure. The nun’s head was bowed as she walked around the perimeter of old St Philomena’s and I assumed that her constantly moving lips were chanting prayers as she fingered the rosary beads clasped in her hands.

As I summoned up the courage to do what I knew I had to, my eyes turned again to look at the disused building’s small windows, which were boarded up with yellowing ply, adding intensity to their derelict state. It was like looking at a familiar face, but with its eyes poked out. I took in my surrounds: rusty corrugated iron, stained concrete, wire netting and high walls. It was like a deserted prison camp. I wondered how a once noisy and busy place could now be so devoid of life. In some ways I felt a little sad because it was a childhood home of sorts. My eyes scanned the yard for the moving nun, the environment heightening my feeling of lonely disquiet, like I had suddenly arrived at the end of the world, with only this nun and myself in existence.

As the nun gradually moved closer, I approached her and asked quietly if I could see inside St Philomena’s.

‘I used to live there when I was a child,’ I said. I waited for the rebuke, but she just motioned for me to walk with her as she continued her conversation with her God. Is she annoyed with my interruption? I wondered, child-like. After a few minutes she looked up at me with a patient look in her eyes.

‘Tell me your name’ she instructed softly. She bowed her head again, this time slightly over to the side I was walking on, a gesture that implied she was ready to listen.

‘Anne Coory’, I replied with inculcated reverence, scared stiff she may hate the name as much as I did.

Expecting her to ask for more information, I quickly went over the prepared details in my mind, nearly missing her almost whispered offering that her name was Sister Joanna and that she knew of my brothers and me. With all the children who passed through this place, what was it about the Coory children’s time there, that a young nun, over forty years later, would know of them at the mere mention of the name?

After a few moments of silence Sister Joanna, in a brighter voice, offered to show me around the other buildings, explaining that we couldn’t enter the dormitory itself as it was structurally unsafe. I began to feel more relaxed and comforted by Sister Joanna’s warming demeanour. This was the first time I had ever been able to have a conversation with a nun as an equal, woman to woman, and somehow this empowered me. The childish awe and reverence had been replaced with calm. I felt the unspoken acknowledgment of my troubled spirit quell my anxiety. Even childhood anxieties about the orphanage and nuns in general melted away as I walked and talked with Sister Joanna. As we rounded the corner of a red brick and wooden building my subdued heart leapt into a frenzy again. I stopped in my tracks. I had instantly recognised St Agnes’ Nursery, with its familiar row of wooden windows, three panes in each.

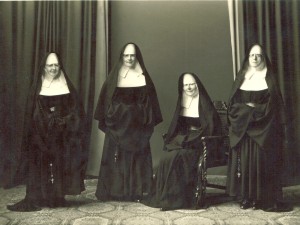

Nursery supervisor Sister Christopher far right. The other three nuns are her biological sisters. (image: Sister Joanna)

**********************************************

My first orphanage home at St Agnes’ Nursery was for babies and toddlers, while the adjacent St Vincent’s housed the older children. The building was of similar construction to St Agnes’ although much larger. Because the children were separated by gender at five years of age, the inmates at St Vincent’s were mostly girls and a handful of boys under five. There were two other buildings in the Mercy complex, which stretched out to the east and behind the Basilica. Orphanages and boarding schools were always built in close proximity to Catholic churches so that daily visits to Mass and prayer were expedient in order to save souls.

**********************************************

Behind the Basilica was the attractive and quite modern looking convent, also built of brick and concrete with a white trim. It was built in December 1901 to replace the old wooden cottage which the Sisters of Mercy occupied when they first arrived in Dunedin on 17 January 1897, a few months before my paternal grandparents Jacob and Eva Coory migrated to New Zealand from Lebanon. The nuns were very proud of their new convent, and it served them well over many years. New additions were added in1945. Those of us who lived permanently within the Mercy complex, devoid of television, radio, and non-Catholic perspectives, were totally institutionalised.

St Joseph’s Cathedral with St Dominic’s Boarding College on the right, at the top of Rattray Street in Dunedin (image: AFCoory)

[When I was nine years old, my father sent me to St Dominics Boarding College]

I told Sister Joanna I had discovered, years later, that the cost of sending me to St Dominic’s was far greater than keeping me here at the orphanage, and that my father was concerned that he couldn’t afford the expense on top of the Sunday Pledge. I overheard my father talking to his Coory extended family (The Family) about it one day, although I can’t recall the conversation in detail. It was clear The Family were not about to assist, financially or otherwise.

Sister Joanna surmised that The Family may have been embarrassed by the fact that a close relative was living at an orphanage for the poor, when their station in life had improved remarkably in recent years.

‘Lebanese families had become very strong within the congregation of the cathedral,’ she told me. The cathedral was adjacent to St Dominic’s College, where many Lebanese daughters attended day classes. ‘Also,’ continued Sister Joanna, ‘at that time Middle Eastern Catholic priests, including those from Lebanon, had begun to train for holy orders in the seminary in Dunedin and were often consigned to duties at the cathedral. And of course the cathedral would have profited greatly from the Lebanese community’s generous financial contributions.’

View of the kitchen double doors leading into St Vincent’s kitchen and dining room. On the left of the picture is the tree in which the mother cat and her kittens were hiding. (image: AFCoory)

My father’s childhood malnourishment caused him to insist Sister Christopher buy the best food for my brothers and me. It was something he was quite obsessive about. We were also to be given daily doses of malt and Lane’s Emulsion, which he supplied. Never-the-less, I still managed to contract scarlet fever, asthma, and ringworm. Anguish was the underlying cause of many of my father’s actions and, I am sure, some of his own ill-health. He harboured a deep resentment toward his extended family over their refusal to care for us while he worked long, hard hours. My father was a simple, uneducated man, but he wasn’t stupid. He could see the injustice and often lamented, when I was a child, that The Family never treated his children the way they treated our cousins. My father had other valid reasons for not speaking to particular members of his family. I didn’t know then of The Family’s history and I didn’t always understand what he was saying. I had no idea that most children lived completely different lives from me and the other children at the orphanage.

Sister Joanna showed much empathy and understanding of the distress I still felt when speaking about my parents. She took my sadness to heart, the fact I never knew my mother intimately and that she and I were prevented from seeing each other. She knew of my mother’s bipolar disorder and that she had spent much of her life in Porirua Mental Hospital, as it was then called. I think my pain was evident when I spoke of the way the Coory family had constantly demonised my mother, calling her a sharmuta (Aramaic word for prostitute). I explained to Sister Joanna that, during all of my research into my mother’s life, there was never anything to suggest that my mother was a prostitute. She did turn to men for love and affection because her own family had rejected her and the Coory family never accepted her. I believe that what went on in Carroll Street when my mother lived there was responsible for the initial severe manifestation of her disorder. She had never known such extremes until that part of her life. I believe that my mother was the scapegoat for all the ills of The Family until she left and I took over the role, much as one takes over a heredity title.

- Read more here in the memoir Whatever Happened To Ishtar? – A Passionate Quest by Anne Frandi-Coory to find answers for generations of defeated mothers, including her own.

Anne and Anthony