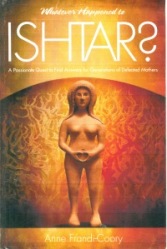

‘Whatever Happened to Ishtar?’ by Anne Frandi-Coory is a necessary read for any mother in order to help make an adjustment to your mindset in this information age filled with books on how to parent better.

‘Whatever Happened to Ishtar?’ by Anne Frandi-Coory is a necessary read for any mother in order to help make an adjustment to your mindset in this information age filled with books on how to parent better.

Anne tells, in an honest and direct way, the reality of her childhood where her mother was largely absent; suffering neglect and abuse in the hands of the Catholic Church and her extended [Lebanese] family. Despite this absence by her [Italian] mother, the rare moments Anne shared with her still gave her something enormous.

It is a balanced account such as she does acknowledge the education the Catholic Church introduced her to.

Why Anne’s story is one of redemption and healing is that, despite what she reveals of her childhood and subsequent adult quest to reach a place of understanding, Anne has in her, a life blood and intelligence that is vibrant and strong. Anne knows how to live in the moment and embrace love and laughter to its full.

Anne is giving back to her children the opposite of what she was given which is a massive testament to her strength and sheer force of character. So if you ever feel you are not giving enough to your child take a read of what Anne didn’t get from her biological parents. Be encouraged by Anne’s story that even the most meagre rations her parents were able to give did make a difference to her. How much more so, an available parent with intent to actively love her children, despite the inevitable mistakes you make along the way? Such a mother Anne has turned out to be, despite all odds.

<><><><

Roseann Cameron, Christchurch New Zealand 25 November 2013

***********************************************************

Read here more about Anne Frandi-Coory’s mother: https://frandi.wordpress.com/2012/04/01/letters-to-anne-frandi-coory/

Read the latest, 4th edition of ‘Whatever Happened To Ishtar?’ published in 2020 HERE:

https://frandi.wordpress.com/category/whatever-happened-to-ishtar-fifteen-reviews/