Excerpt from ‘Whatever Happened To Ishtar?; A Passionate Quest To Find Answers For Generations Of Defeated Mothers’

…

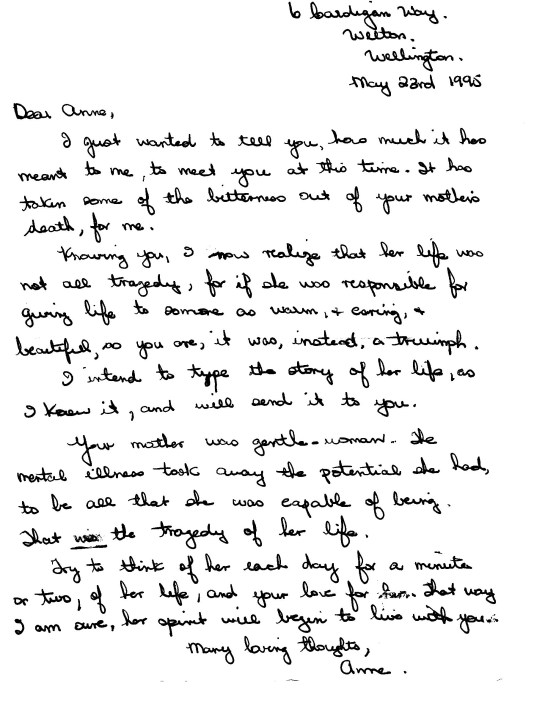

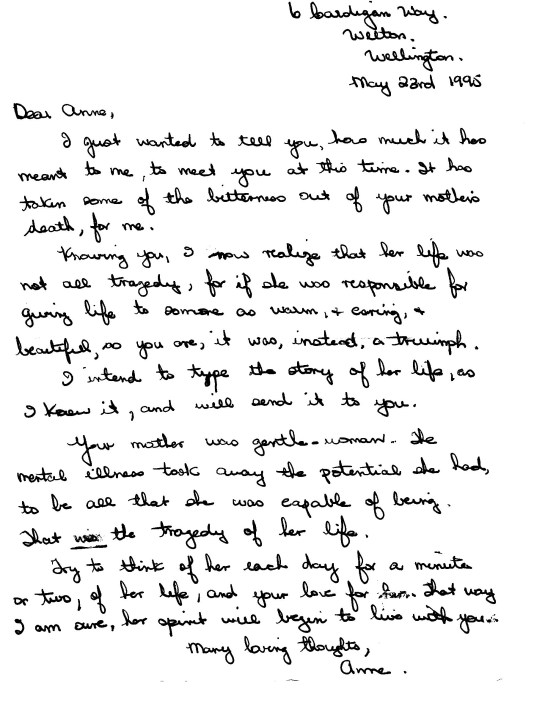

The following letters were written by Anne Frandi Albert to her niece, Anne Frandi-Coory, following the death of her mother, Doreen Marie Frandi. Anne Albert died in 2001 shortly after writing the last of several letters to her niece, but if she had not met her niece at Doreen’s funeral. the two would not have known each other and there is so much about Doreen’s life that her daughter would never have discovered.

><

***This page is ©copyright to author Anne Frandi-Coory. All Rights reserved 1st April 2012. No text or photograph can be copied or downloaded from this page without the written permission of Anne Frandi-Coory.***

><><>

Doreen Frandi, Maria Frandi (mother of the other 3 women) Betty Gentz, Anne Albert

***************

**************

Doreen was such a beautiful child that on the ship which brought her, her brother and parents to New Zealand, a genuine childless couple offered her parents money to allow them to adopt her. Doreen had a cloud of bright red curls that framed her pretty face. How different Doreen’s life would have been had the adoption gone ahead. Life within the Alfredo Frandi family was an uneasy one, so inclined was he to uncontrollable bouts of violent rage, during which he would throw furniture around the room and punch holes in doors. Often it was his wife, Maria, a pale and nervous woman, who felt the force of his fists. Maria was in a perpetual state of acute anxiety and her concern about their lack of money exacerbated this state. Alfredo was a labourer and work was hard to come by. They had four children they could barely feed and clothe so any subsequent pregnancies were aborted with a knitting needle. Unfortunately, as the oldest daughter, Doreen was needed to assist with the cleaning up after these procedures. Maria had no conception of the trauma this was causing her daughter, and which was to haunt Doreen for the rest of her life.

When Doreen was sixteen years old, I was born, but I have never quite known why I was not aborted. I can only suppose that my mother may have been experiencing symptoms of the menopause and may have been unaware of the pregnancy in time. So unexpected was my birth, that an apple crate was all that my parents had to lay me in. Doreen was thrilled about the new baby and set about lining the crate with material and making it look pretty for me. This was the beginning of Doreen’s devotion to me which was to last all her life.

Doreen was a very gentle girl and she was a help to her mother in caring for the younger children, but she loathed house work of any kind. She was adept at shopping for bargains and was a very good sewer. Catholicism began to influence her life early on, as it brought her a peace and beauty so missing from her home environment. Significantly, the nuns at the convent school she attended, recognized her potential for a vocation and one nun, Sister Anne, encouraged Doreen all she could to think about entering the convent. As Doreen approached womanhood she exhibited no interest in boys or other worldly things, so firmly were her sights set of becoming a Catholic nun. Alfredo was dead against his eldest daughter becoming a nun and turned the house upside down to show how much he detested the very idea. This turmoil only made her more determined, and after a short time working in a department store and following her debut at the annual charity ball, for which she made her own stunning gown, Doreen entered the convent.

><><><

Doreen’s Debut in the dress she made herself

><><><

Initially Doreen loved her life as a nun, but after almost a year of doing nothing but housework, she asked if she could train as a nurse. Her wish was to care for severely handicapped children. However, her request was greeted with profound disapproval because to actually ask to be able to do what one wanted, was against the very strict rules of the convent as well as a denial of the vow of absolute obedience. Doreen was severely reprimanded and as a result sunk into a deep depression. The nuns could not understand Doreen’s depression; they believed that if you had a true vocation faith was enough to protect you from such things. They then put pressure on Doreen constantly questioning her commitment to her vocation. Doreen became hysterical which appalled the nuns, and they subsequently demanded that her mother remove her from the convent. They could not know that bi polar disorder was manifesting itself in Doreen and would consequently ruin her life.

Doreen recovered very slowly from her first breakdown but she was devastated that her vocation was at an end and that she had broken her vow to God. Doreen did finally find acceptance and there followed a succession of jobs, which began a pattern set for the rest of her life; employment interspersed with breakdowns. In the 1940’s not much was known about bi polar disorder nor were there any satisfactory drugs available at the time. Doreen was then subjected to countless ECT treatments without anaesthetic which really amounted to torture. Around this time Doreen’s Aunt Italia, Alfredo’s only sister who was then 70 years of age, decided to take more of an interest in her niece. Italia regaled Doreen with stories of the privileged life the Frandi family lived in Italy before they arrived in New Zealand [Italia was born in Pisa, Italy in 1869]. Aristodemo, Italia’s father, had to flee Italy because he was a political agitator alongside Garibaldi, and Italia showed Doreen the fine silver and linen they had brought over with them. Italia also dazzled Doreen with stories about the family riding in a grand carriage and people bowed with respect for them. Whenever Doreen was in the manic phase of her illness, she had illusions of grandeur, and would repeat all that her aunt had told her about their previous life in Italy. In these early stages of her illness, Doreen would spend money she did not have and would charge up accounts to her Aunt Italia and sometimes even stay in expensive hotels, all charged against her aunt’s name. Following these episodes Doreen would then sink into the depths of depression.

Shortly before the end of the war Doreen joined the Air Force. It was while she was in the Force that Doreen met the father of her first child, Kevin. Phillip Coory neglected to mention that he was already married with a young son, Vas, until Doreen informed him that she was pregnant. Phillip Coory believed at the time that that was the end of the matter and he had rid himself of her, but then his brother Joseph came on the scene. Joseph was a kind and simple man, who did his best to make Doreen happy. Sadly, his family conspired against Doreen from the outset; perhaps they did not approve of her good looks or the way the marriage came about. The marriage ended in disaster; Joseph was not her intellectual equal and her illness would have been extremely difficult to live with. About three years after their marriage Anne was born and eighteen months later, came Anthony. Following a severe bout of bi polar disorder, the children were taken from her and placed in an Orphanage for the Poor in South Dunedin.

The permanent loss of her children caused Doreen great anguish from which she never really recovered. In later years she had contact with her daughter Anne, but Doreen was never able to accept that the child did not blame her mother for her abandonment. Years later, her youngest son, Anthony moved to Wellington to live, but that feeling of guilt never left her and obviously prevented her from having an emotional relationship with her son, although he did make a futile attempt at it. Doreen and Kevin lived a life of great hardship and near poverty, with Doreen frequently suffering nervous breakdowns, which culminated in her being admitted to Porirua Psychiatric Hospital. Kevin had to learn to deal with his mother’s extreme mood swings from a very early age which made his young life intolerable at times. I have no idea how she coped during those years but I am sure that sometimes she must have prayed for death, yet through it all her faith in God never wavered and carried her through until the day she died.

At the peak of her loneliness, Doreen met a man, Edward Stringer, and spent a night with him. Of course, given her luck, or lack thereof, it ended in pregnancy. During the weeks after the birth of her daughter, Florence, and suffering from depression, Doreen signed adoption papers for her daughter. Sometime later, Edward and Doreen met up again, and with the sole intention of getting her daughter back, she married Edward. Heartbreakingly for Doreen, it was much too late; the adoption was quite legal and binding. Once again life had defeated Doreen and during a severe bout of mania, Edward left, unable to cope with his new wife’s disorder. From this, there followed a period of dreariness, when Doreen and Kevin lived in a state house at 56 Hewer Crescent Naenae, Lower Hutt in Wellington, and she obtained a reasonably stable job in a factory close by. At least the disorder left Doreen in peace for an extended period, in which Doreen developed a love of cats, and she had up to six at one time or another.

Kevin started up a very successful restaurant, Bacchus, in Courtney Place in Wellington. Doreen was employed by Kevin in the kitchen of the restaurant, and she appeared to enjoy her time there. Sadly her mother died on 10 March 1980, which caused Doreen to have another nervous breakdown. Following her recovery, Doreen retired from work and moved into a council flat in Daniell Street, Newtown in Wellington. During this time, she appeared to me to be doing no more than going through the motions of living. My heart ached to see her like that, with no apparent interest in anything. Kevin’s bankruptcy and his consequent permanent move to Sydney, took the utmost toll on her spiritual well being. Doreen then lapsed into a serious bout of her disorder, suffering yet another complete nervous breakdown, and she was admitted once again to Porirua Hospital for a considerable time.

I have no doubt whatsoever, that it was not only Doreen’s manic depressive illness that had such a destructive effect on her life. I sincerely believe that she carried guilt feelings from her experiences as a young girl, witnessing her mother’s self inflicted abortions, made worse by Doreen’s Catholic beliefs. I realized this to be true, with great clarity, when I visited her at the hospital during her final stay there in 1995. She led me out into the hospital gardens, and pointed to a bed of purple pansies in bloom. “There you see” she told me with infinite sadness, “there are all the little babies” – Anne Albert.

><><><><

*****************************

Whenua Tapu cemetery, Wellington, New Zealand

*********************************

********************************************

Doreen’s Children….

Kevin Coory

Anne and Anthony Coory

Florence – adopted out (now Hudayani Gleeson)

Bruce – adopted out (now Bruce McKenzie)

**************************************

More: ‘Whatever Happened To Ishtar? – A Passionate Quest To Find Answers For Generations Of Defeated Mothers’