The Blog Comments below were posted by David Edward Anthony, USA on page:

**********

David Anthony:

I LOVE your website. I’m of two worlds, too, in this case 1/2 Lebanese and 1/2 Irish. The Lebanese side arrived in the USA from Lebanon in 1892.

Amelia Coory, Joseph’s sister who died from TB at 17 yrs old.

The photo of Amelia Coory looks so very much like one of my cousins (who is 1/2 Lebanese and 1/2 Italian). Similarly to Amelia, my sitoo’s [grandmother] brother Peter died of “exposure” in the 1890s. He was perhaps 10 years old. In the USA at least, there was a terrible depression (the “Panic of 1892”) that led to widespread unemployment. In my great-grandparents’ case, they couldn’t get work have to live outside in a lean-to in the winter- it probably led to my grandmother’s brother’s death.

I see you have a Khalil Gibran – inspired drawing at the top of your page; interestingly enough, there are Gibrans in my family’s old parish.

Sketch by Khalil Gibran

Anne Frandi-Coory:

Hi David, good to hear your story. Khalil Gibran was born in my grandparents’ village in Bcharre and moved to USA when the Catholic Maronite minority were suffering persecution by muslims. We are related to his family through marriage [Khouri]. If your family came from Bcharre there is a good chance there will be a family connection because my grandfather’s sisters emigrated to the US. Lebanese/Irish combination would make for a volatile mix as does Lebanese/Italian, I would say?

David:

Hi! Thank you so much for the reply.

Yes! Irish-Lebanese is a volatile mix! My Irish mother could be very much the unstoppable force where my Lebanese dad was the immovable object. When she got excited, it was like a tornado was set loose in our living room- and that Tornado came up against the Mt. Everest that was my dad!

My family isn’t from Bcharre. It’s from a very similar town not that far away to the west- a town called Ehden.

I hesitated- strongly- on telling you about Ehden as Bcharre and Ehden are two very similar towns – Maronite Catholic and set in the mountains- photos of both towns make them even look similar- but they historically are two rival towns as well. I suspect you’ve heard in your life how Italian towns are rivals- very similar thing.

Both Ehden and Bcharre are *very* ancient towns. Both rightfully can boast an ancient heritage- with ancient buildings and such. Bcharre, if I remember right, boasts the oldest cedars in existence (and among many things, of course being the birthplace of Khalil Gibran)..while Ehden, for example, hosts Horsh Ehden, a very ancient nature preserve, and also the oldest Maronite church in the world.

Now, the reaction of many old Bcharre people on hearing from someone from Ehden is usually something like, “Ehden! Those people are NO GOOD.” Which goes back to the book, The Arab Mind* and the author’s conclusion that there’s really not much middle ground between liking and dislike in the Middle East.

I hope (!) that my telling you I’m from Ehden (really Zghorta, which is its mirror town – Zghorta in the winter and Ehden in the summer) doesn’t give you a bad vibe!

Anne:

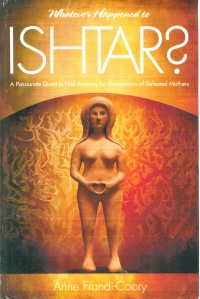

I was a bit like your mum when I was younger-very fiery, not sure many people understood me. But I didn’t inherit the ethnocentricity that my grandparents brought with them from Lebanon because I spent my formative years in an orphanage. My mother became mentally ill (not surprisingly) and dad’s family didn’t want me because my mother was Italian. However, I love the Lebanese people and the Italian people and consider myself blessed, and I am proud, because of the wonderful positive traits I and my children have inherited. Writing Whatever Happened To Ishtar? helped me to see that. So, David, the fact you are Lebanese is fantastic!

*READ my review here:

David:

I’ve read this book as well – about two years ago. It helped me, too, connect to my Middle Eastern roots. As I’m half of Irish descent, and the Irish side of the family being HUGE, I tended to spend far more time with the Irish side than the Lebanese side. Plus my father, a very kind man, tended to be a very reticent man. As the Lebanese side of the family was very small, I tended to not get hardly any exposure to the Lebanese side; even though, quite frankly, I looked *very* Lebanese. I kind of stuck out when visiting my Irish cousins! 🙂

I remember reading in the above book an account that the author witnessed of Middle Eastern people leaving a movie theater. People leaving the movie often showed no middle ground. They either LOVED the movie, or they HATED it. That lack of a “middle ground” is very close to my own personal experiences- and reading the above, it seems that you had similar experiences? Either they accept you wholeheartedly..or not at all. Growing up, it confused me. I saw people being what I called “favorited” or not favorited at all. It took me many, many years (and some hurt) to figure out what was going on.

That said, I didn’t know that the tidbits of language I had picked up from my jidoo [grandfather] weren’t really Arabic until I was an older teen. What happened was that a distant cousin north Lebanon visited our family. When he spoke to my jidoo, they couldn’t understand a word they were saying to one another. My jidoo was raised to speak what he was believed as Arabic from a young age- in fact, it was his first language. Why couldn’t my cousin from Beirut understand him?

In the end, we figured it out. My cousin spoke modern Arabic. My jidoo spoke a form of Aramaic that was spoken more than a century ago, which was passed onto him in the USA by his family. Not only was my jidoo speaking another, older language, he was speaking a form of it that was about a century old!

I really like your site. I don’t have much time to check it out from top to bottom; I hope it’s okay if I come back and read through it some time! Thank you for posting so much interesting stuff!

Anne:

Here in my review of another book you may be interested in: