Excerpt from ‘Whatever Happened To Ishtar?; A Passionate Quest To Find Answers For Generations Of Defeated Mothers’

><

Wherefore hidest thou thy face?…Wilt thou harass a driven leaf? Job xiii: 24-25

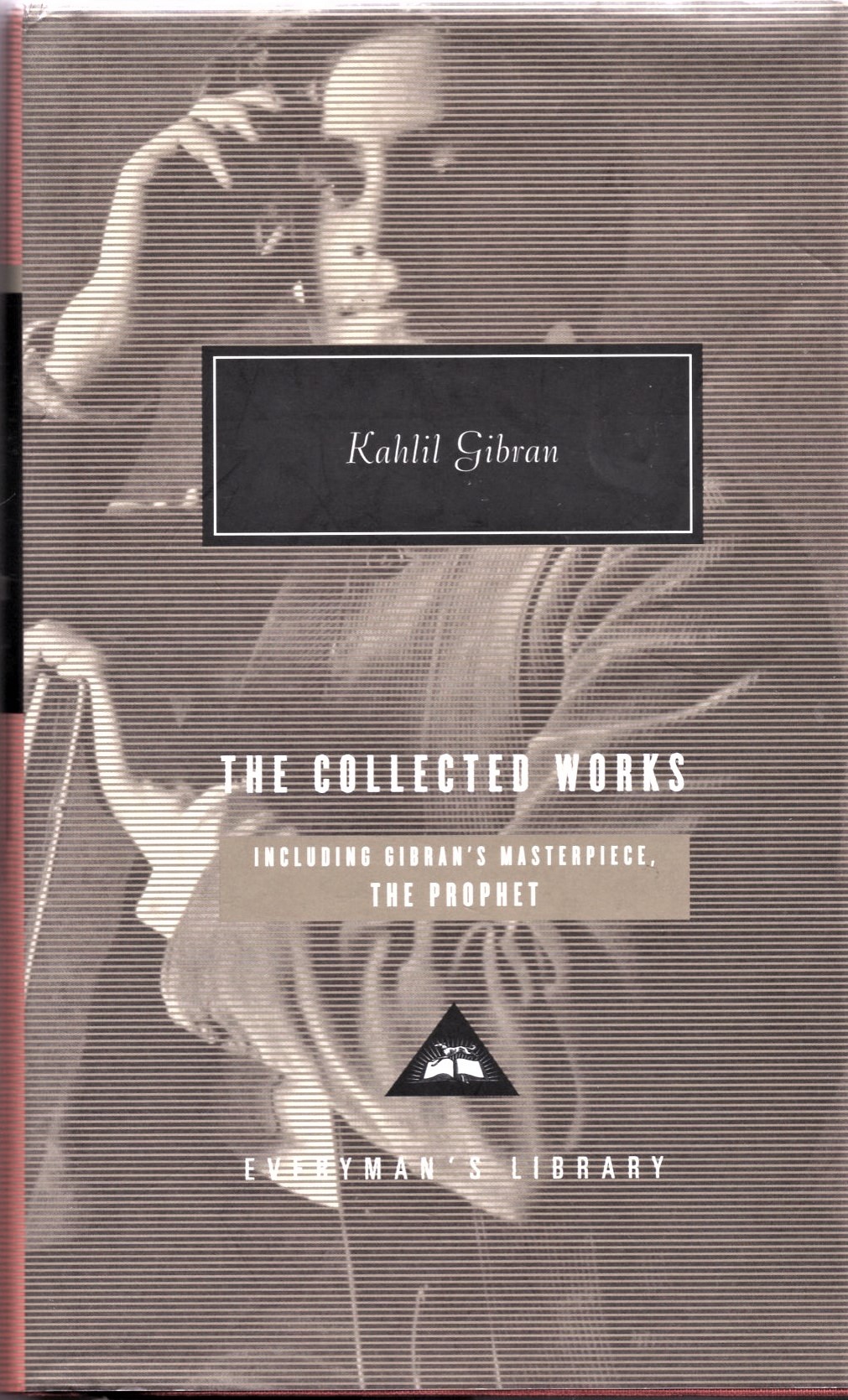

….But you should also be proud that your mothers and fathers came from a land upon which God laid his gracious hand and raised his messengers. – Kahlil Gibran, I believe in you (1926)

><

***This page is copyright to author Anne Frandi-Coory. No text or photograph can be copied or downloaded from this page without the written permission of Anne Frandi-Coory.***

><><

When I was a child, my father’s was the face I searched for whenever I heard heavy, non-nun-like footsteps echoing on the highly polished floors of the orphanage. I was always and forever tuned into the sound of footsteps. A nun’s footsteps sounded lighter, stress-free, and somehow patient, like they themselves were. It was as if they had all the time in the world to get where they were going, praying as they went.

Once I was alerted that a nun was on her way, I would strain my ears for the accompanying rhythm, in tune with a particular nun’s footsteps, of the rosary beads clinking with the heavy crucifix hanging from a belt around her waist. I would know who she was before I saw her face. A visitor’s footsteps, on the other hand, were usually more purposeful, more intent on their course. Perhaps it was someone wishing to get the visit over with, to leave as quickly as possible. The fact that there were many children living there didn’t make the place any less sombre. Colours were an unnecessary luxury. ‘Interior décor’ was a phrase out of place and out of mind in that institution. My father, Joseph Jacob Habib Eleishah Coory, rarely visited me and I learned very early on not to expect to see anyone other than the Sisters of Mercy, day in and day out. Occasionally, a priest would visit the orphanage but I rarely had any significant contact with them. They were, as far as my child’s mind could fathom, so close to God and so holy that they would not want to bother with me. The nuns reinforced this perception by their subservient attitude whenever a priest or bishop made an entrance. But when my father came to visit me, I would feel a strange kind of comfort, almost a feeling of surprise, at the sight of him.

*****

Anne’s father, Joseph Coory with his beloved dog Tim, outside his house at 103 Maitland Street, Dunedin NZ.

All through my childhood, I would reach out for his emotional support. and in his emotional immaturity, he would reach out for mine. As young as I was, I always sensed that he needed me as much as I needed him. In this way, we both survived my childhood. Perhaps it was my concern for him and his whereabouts when he left me that caused me so much anxiety. He could never stay for long and his leaving always caused my insides to churn, which I never really learned to deal with. A Catholic orphanage was not the sort of place where your emotional needs were attended to. The most important thing here was the health of your soul. My father always seemed harassed and a bit lost, so eventually I avoided scenes of tears because it would only upset him. I had no idea what was happening to my father on the outside of the orphanage but it didn’t stop me from picking up on his moods and demeanour. Children like me become very adept at internalising emotions and hurts. But there were times when the dam burst, causing me to scream and yell so much that the nuns would lose their patience and lock me in a cupboard or a small room. There was always that air of emotional fragility about Joseph, my very being attuned and attentive to his every nuance. Too soon I would become the adult and he the child. Perhaps this was why I took so long to deal with my own emotional needs.

><

><

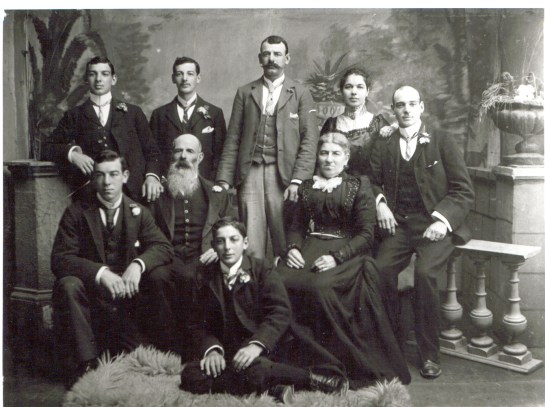

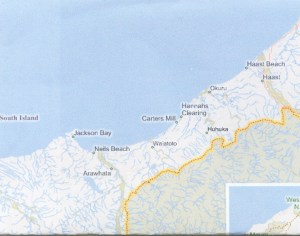

Jacob and Eva Coory’s firstborn son, Joseph, followed two daughters, Elizabeth and Amelia. But sadly Joseph was not the healthy son his parents longed for. His sickly entry into the world was one of the reasons he suffered ill-health all of his life. According to his father’s diary, written in his native Aramaic, Joseph almost died when he was a newborn. He was so ill during his first two years that his mother wrapped him warmly and tightly and waited for him to die. Joseph suffered ill thrift all through his baby and toddler years because he could only suck small amounts of milk, sometimes bread soaked in milk. I was later to discover that Joseph’s birth had never been registered so there is no doubt that his parents expected that he would die. From his childhood to his death, he never ate a balanced diet, ever. He existed instead on bread and cheese, some fruit, and endless cups of sweet milky tea. He was a simple man who attained the literacy levels only of a twelve-year-old. But he could speak English and Aramaic fluently. He left school at the age of nine and refused to return because of the beatings he says were meted out to him by the Christian Brothers. As a young boy he only spoke comfortably in Aramaic, so language was definitely a barrier to his learning. It has been confirmed by his cousins that his parents refrained from disciplining him because of his fragile health and that he, quite literally, got away with doing almost whatever he wanted to do at home. He in turn clung to them for the rest of their lives and he never left The Family home at 67 Carroll Street in Dunedin, where he was born.