***** Please Note: Text and images copyright to Anne Frandi-Coory – All Rights Reserved 4 January 2019.

Q7. Did you witness other incidents, forms of abuse (psychological, physical/violence, sexual) by nuns or others there, and if so, how often and against whom?

A. The kinds of child abuse I witnessed at the Mercy orphanage were more psychological and emotional; traumatised little children being re-traumatised over and over again, by religious women dressed in intimidating habits, who offered us no love, or affection, no comfort and who also allowed us to suffer from gross neglect. They terrorised us into submission and into ‘holiness’ and ‘piety’… These issues must have been raised by other children incarcerated in these orphanages, in the years since, because Sister Joanna volunteered in 1992 when I met her, that Sister Christopher, who managed St Agnes Nursery, was “far too busy to give individual children special attention.”

An example of the psychological and emotional abuse involving my brother Anthony and me at the Mercy orphanage occurred during one of the only times I remember both Joseph and Doreen visiting us at the orphanage in c.1952 when I was around four and a half years old, Anthony three years old. Joseph and Doreen brought Kevin with them, but I am not sure where Doreen and Kevin were living at that time. We were taken to St Kilda beach playground where Doreen took a photo of the three of us children on a swing. I remember that day, because we were all together, we had equipment to play on and we were given the very rare treats of ice creams and soft drinks, and Kevin told me many years later that it was one of the happiest days of his childhood.

Afterwards, Anthony and I were dropped at the entrance to the convent, but Anthony was starting to cry, he didn’t want to leave Doreen, to whom he clung. The nuns instructed me to take Anthony inside to the toilet.

All the while my heart was breaking because I didn’t want them to leave us there. I took Anthony to the toilet but when we came out, and he saw that Joseph and Doreen had gone, he screamed and screamed, the tears streaming down his little pale face…I started to cry as well, but the nuns offered no comfort, told me to stop that nonsense (or words to that effect) and dragged Anthony off to the nursery and told me to go into another room. It took me days to get over this, but I was not allowed to ask about my mother. My brother and I were not even permitted to comfort one another.

On another occasion, I was sitting on the floor with other children and there was a nun sitting in front of us in a chair, when another nun came in carrying a small gold bangle, approached me and told me that my mother had arrived at the door of the orphanage with the bangle as a gift for me. The nun tried to get it over my hand but it was too small. I was too frightened to ask about my mother, who I wanted to see, and then I saw the nun put the bangle up high in a cupboard which I knew I could never reach. Once again, I bottled up my feelings of, how shall I describe those feelings…infinite sadness, and when I did summon up the courage to ask the nun, after she had put the bangle in the cupboard, if I could see my mother, she replied that no, she had already left.

I remember a little girl in my primer class, Ann Tye (of Asian descent), who like me, was laughed at and bullied by other children because we wet our pants and obviously stank, yet the nuns treated us as though we were ‘sinners’ or ‘lepers’ which I certainly felt like, and who failed to provide treatment for us or to protect us, or even to clean us up. The nuns never ceased to tell us stories about lepers in colonies that Catholic missionaries ‘looked after’ and I certainly believed, from what they told me, that lepers were sinners and that the sores they suffered from were as punishment from god and that missionaries were there to convert these ‘pagan sinners’ to Christianity so that they might be cured. I cannot stress enough the harm these ‘stories’ caused us already ‘suffering’ children.

St Patrick’s Primary School class in orphanage complex

We learned about the intimate lives of saints, how they were tortured and died because they refused to deny god or Jesus. All of these saintly stories were designed to keep us pure and to provide role models for us children. To sacrifice ourselves for Jesus or god, was to ensure that we entered the kingdom of heaven when we died so I aspired to be a chosen one after movies we were shown of ‘unblemished’girls in biblical times, being chosen for sacrifice.

We had to help cook meals for all the children when I was living at St Vincent’s wing for junior school girls which was then managed by Mother Boniventure. I believe I was around six or seven years old. Another girl and I had helped to prepare and cook lemon sago pudding for dinner, and as she removed the heavy, boiling dish from the oven with oven gloves on, which I remember were huge, she dropped the boiling dish and I watched in horror as the sticky orange goo slowly ran down her bare legs as she screamed. There was chaos everywhere and later an ambulance came and took her to hospital. When I next saw her, her legs were covered in bandages. I will never forget that smell of lemon sago pudding which we all hated!

The thing is, we were little slaves, and the impression I was left with was that we were worthless and that no-one really cared what happened to us. Our mothers were ‘fallen’ women, and in so many ways, we were reminded of this daily. Very few children were actually orphans …and some children were there because their mothers were ill, or who had died, and they were the ones who went home for holidays. On the other hand, children like me, whose mothers had ‘sinned’, well we knew we were different, because we were treated with indifference.

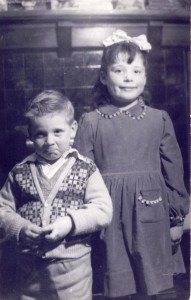

Anne Frandi-Coory 5-6 years old…note the squint.

Q8. Can you describe the atmosphere of the place and the impact you saw this experience having on others around you?

In the Mercy orphanage, it was that lack of affection, the knowing that we were not special to anyone, and the nightmares we experienced. I especially remember the nightmares, of burning in hell, and that god would not bring another flood to the earth, like he did in the bible, as the nuns and priests loved to tell us; no, the next time humans were bad, it would be the end of the world and there would be fire like the fires of hell. Every time we heard fire engines, we thought it could be the end of the world. There were those children who were dressed better, and who spoke with better diction, and had better vocabularies, than those of us who were abused and traumatised. They went home for holidays and the nuns and priests favoured them; that was obvious to us, the cursed ones.

St Philomena’s Dormitory for girls in Macandrew Road, South Dunedin

The Mercy orphanage was always busy with people; children, college girls, nuns, priests, visitors. I also remember large dormitories, with rows of beds, and when I was a toddler, I remember many cots in the nursery, not in rows, but placed this way and that and I was probably more than three years old and still sleeping in a cot, because I can remember standing up in the cot for what seemed like hours. Most of us were scared of the dark. We were not happy children … and we didn’t have toys or play equipment. We didn’t even know how to play, or to smile. When photos were taken, and someone said smile, I honestly didn’t know how to. My most vivid memories are of children crying and us small children polishing floors, and me waiting for Joseph to visit me. We hardly ever ventured outdoors.

Kevin’s First Holy Communion

When I was a boarder at St Dominic’s, around 1957, the whole building began to fill with smoke, and we children were all terrified that the building was engulfed in flames. We heard sirens and nuns rushed in and ordered us to vacate the building at once. We all raced down the stairs and out onto the concrete steps behind St Joseph’s Cathedral. We had been in bed and were half asleep, so we were all shivering in our nighties standing outside on a cold winter’s night. This seemed to go on forever, with firemen running in and out of the building and nuns seemingly rushing about everywhere, red faced and in mild panic. Once everything had calmed down, we were instructed to go back to bed, it was only a chimney fire which had been caused by a blocked chimney which hadn’t been cleaned for some time.

The dormitory at the rear of St Dominic’s College and the boarded up dining/kitchen area.

When we were back in bed, lacking comforting words to allay our fears, the girl in the bed next to mine began to talk about how frightened she was. We discussed what it would it be like at the end of the world when it was all on fire and there weren’t enough fire engines to put all the fires out. We stayed awake for hours after that; I am sure her heart was racing as fast as mine was. We talked about animals and birds and people being burned to death. It was a long night.

Q9. What was the impact on you at the time? And since then?

Fear and loneliness were what I lived with every day as a child … fear of things, fear of the end of the world, fear of dying, fear that the devil and god were always watching me, fear of animals. I was so afraid of the dark, because I often ‘saw’ the devil watching me to see if I was a bad girl. Many were the nights I lay awake in terror, hiding under the bed covers, with my heart pounding in my throat, after a nightmare. I was even afraid to go outside at night because I believed that either god or the devil lived on the moon; I could see someone there…and I was always sure that the moon followed me in the dark.

Anne Frandi-Coory in Mercy Orphanage clothes aged about eight years old

One of the worst nightmares, which recurred again and again during my childhood, was of me sitting on a swing which was swinging higher and higher, and I am screaming for it to stop, while trying to look around to see who was pushing the swing, but I could never see who it was although I knew someone was there. Another recurring dream was me being locked in a tiny space, my screaming waking me up. This happened once when I was staying at my cousins’ house when I was about 13 years old, and my screams woke the whole house.

I would sit alone somewhere, completely zoned out, I don’t know in what mind space, so that if someone called me, I couldn’t hear them. This happened many times and often I was punished for not coming when called. I suppose it was no wonder that my family, nuns and priests thought I was ‘backward’.

Anne Frandi-Coory 10 years old

I was still afraid to go to the toilet and continued to wet my pants until I was about 11 years old. We didn’t have access to animals or birds, and knew nothing of the natural world. We were never read nursery rhymes or fairy tales, so in later years when my children were young, I used to read to them every day, and I learned so many fairy tales and stories that I’d never heard of. … the only stories about animals that we heard in the orphanage were abstract e.g. St Francis loved animals and birds, and sheep and goats were looked after by shepherds.

As a young mum, (I was married at 18 and gave birth to my first child at 19) I’d race to the church to have my babies baptised, because I ‘knew’ that god would take them from me if I didn’t have them baptised asap and that they would go to Limbo forever. I was still having nightmares about the end of the world and of one or more of my children dying. I was jumpy and over emotional, with a very quick temper…I could become very angry over the slightest thing, which often left me screaming and crying. I felt intense pressure to be a good mother which was the cause of much anxiety and depression on my part. I asked our family doctor if he could help me, but he didn’t suggest counselling, which now when I think about it, he should have done. However, he prescribed me amitriptyline in 1972, which calmed me down and I did sleep better. I stopped taking this medication in 1980, and later I consulted psychologists; the best and most helpful was John Craighead who worked from the public hospital in Blenheim, Marlborough. I remember well my opening words at my first appointment with John Craighead: “I have been paying for my mother’s sins for years” …his silence was deafening.

Anne Frandi-Coory 23 years old with three of her four children

Up until the late 1990s, a nightmare, a triggered memory, could make me cry for what seemed like hours, but the next day the depression that had been building, would lift, until the next time. All through my childhood, and early adulthood, I was socially inept and behind all of my peers in all other milestones. I was bullied at school, laughed at, humiliated and had no close friends all through my school years. However, I could read, I loved learning, especially English grammar which I excelled at, and once I learned to read, I stole children’s books from cousins and a neighbour, and sometimes to be alone, I’d take the books and sit somewhere alone to read them. I am an avid reader but this has had its drawbacks, especially when I was younger. I take things literally, which often caused confusion and which meant I was very slow to understand colloquialisms and sarcasm.

I find it difficult to engage with people I hardly know, at an intimate level, because of trust issues. I am a virtual recluse, with only a few close family members and my life partner sharing my life. I loathe being the centre of attention so social media and writing are very important aspects of my life.

I experienced anxiety, nightmares, panic attacks, a deep sense of loss and fears of abandonment, interspersed with bouts of crying, which abated in my forties. I had attended Canterbury university in Christchurch, enrolling when I was 42-years-old, commuting from my home in Marlborough, with the support of my partner. I started a degree in psychology, but I changed my major to sociology because I wanted to understand more about life and the socialisation process. I completed my degree through Massey University while working for Social Services full time in Blenheim. It was around this time that the nightmares finally ceased. I felt safe and secure…but the journey was too long and too arduous.

Q10. Why was your Italian mother never allowed to visit you? Did you know this at the time, or just wonder why she never did?

According to my paternal Lebanese family, my mother was a ‘sharmuta’ (a prostitute) and needless to say my father passed this information onto the nuns at the Mercy orphanage. There was no secret about my mother being a ‘fallen’ woman, and although I didn’t fully understand what those particular words meant, I knew they were about sinful, impure women; we as children had been read many stories of what happened to sinful women.

Doreen Marie Frandi

Doreen was evicted from the Coory house at 67 Carroll Street for some reason, and I have listed Kevin’s and my thoughts on the possible reasons above. Kevin was 3+ and I was ten months old and it appears at that time she was about 6 weeks pregnant with Anthony. I saw Doreen a couple of times as a very young child; Joseph occasionally took me to visit his family at 67 Carroll Street and while I was there on one occasion, Doreen crept down the concrete steps at the side of the house, and found me in the rear yard, where she smiled her dazzling smile and gave me three picture books, said goodbye and left. I was perplexed, and when Joseph asked me where I got the books, I told him about the lady with red hair… ”Oh, that was your mother” he said, but I truly didn’t understand who or what a mother was then. Then later there was the trip to St Kilda playground, one of the few times we were all together, parents and three children. I knew she was my mother at that stage, and I loved being with her.

I think I understood while still living at the orphanage that Doreen was a sinful woman and that is why she wasn’t allowed to see me, but of course I didn’t understand then, what she had done to make her a “sinful, impure” woman. If ever I asked Joseph why he and Doreen were not together he would just say that “she broke my heart” and my aunts would tell me that she was a sharmuta. Although I didn’t fully understand the meaning of that word, I knew it meant something very bad.

My father took me to visit Doreen a few times; when she lived in a boarding house in St Kilda at the corner of Forbury Road and Valpy Street, where I remember Joseph taking me up a curved flight of stairs, and he obviously had been there before, because he knew which room Doreen lived in. I have a stark memory of standing there in front of her and watching her smoke one cigarette after another, while she chatted to me. And once when I was about three years old he took me to visit her in hospital after she had been knocked over by a car and had her leg broken. She always had a warm smile for me. However, I knew not to tell the nuns or the Coory family about these visits.

Q11. Did you have contact with your mother later in life?

I met my mother occasionally when I was a teenager and after I was married, usually at her state house in 56 Hewer Crescent, Naenae where she lived with Kevin, later at his house after he married, and not long before she died, at her government flat in Newtown, Wellington.

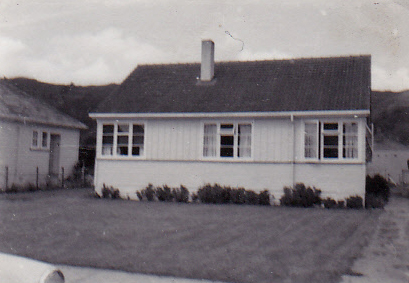

56 Hewer Crescent, NaeNae, Lower Hutt

Joseph died in December 1974 and I went to his funeral, although Doreen didn’t attend. However, the following year in 1975 she flew to visit me and my family in Marlborough. She was very well then and on medication for her bipolar disorder. It was only for a few days, but it was very healing. We talked a lot about her marriage to Joseph, and when she had custody of the three of us children in Dunedin.

At that time, I hadn’t done any research for my book ‘Whatever Happened To Ishtar?’ so I knew nothing of her Italian background, her childhood etc, so our conversations were concentrated around her marriage to Joseph, and my birth. She told me that I only weighed five pounds at birth but that I quickly doubled my weight, which astounded everyone. While she was pregnant with me, Joseph raced around to shops to buy the food that would satisfy her cravings and that she lost a lot of blood during my birth. She breastfed both Kevin and me. I didn’t ask more about Anthony because I did not know much about him, apart from when he was a baby, and a very small boy. These conversations conveyed to me that she tried to be a good mother, she had done her best with what she had, and photos of Kevin as a baby, show a happy, chubby boy. There are no photos of Anthony or me as infants.

Doreen told me that Joseph was good to her at first and that she believed having a daughter “made a man a man”, but apart from that did not say much about the Coory family or why they evicted her and I didn’t like to ask. She talked about being admitted to Porirua Mental Hospital as it was called then, and how during one admission, she screamed out that the lady in the other bed was her sister Anne (whom I was named after) although the staff did not believe her and told her to stop screaming. Finally, Aunty Anne saw her, and she began to scream as well. Anne was suffering from severe depression. Doreen had become a nun at nineteen, to escape the violence at home; her mother was sexually abused and beaten by her father, and one day he dragged Doreen, the eldest daughter, out of school at 13-years-old to take care of her siblings and her mother. She witnessed her mother self-aborting with a knitting needle on more than one occasion and was forced to clean up the bloody mess.

Of course, entering a convent when she was 19 years old, did not help Doreen (then called Sister Martina) to escape from the realities of life as she had hoped. She left the convent a very naïve and troubled woman, but remained a devout Catholic from then on, which I believe hindered her rather than helped. Doreen prayed endlessly, instead of seeking the professional help she so desperately needed. She subsequently spent the next few years looking for love, but instead was used and abused by several men. I believe that Joseph did love her, but he was a simple man, socially unaware, with the vocabulary and reading age of a twelve-year-old. He certainly had no idea how to treat a woman or how to raise children! Doreen kept in close contact with an order of nuns when she moved to Wellington, until the day she died.

Doreen said that she never stopped thinking about us children and when Anthony and I were taken from her, and she was forbidden to have any contact with us, it worsened her illness and caused her to be deeply depressed. She also told me that it was Joseph who originally placed us children in the Mercy orphanage. This and other information was verified by Doreen’s psychiatrist, Dr Bridget Taumoepeau at Porirua Psychiatric Hospital when I spoke to her in 1995 about two weeks after Doreen’s funeral. She told me that whenever Doreen was admitted to the hospital “she never stopped talking about Anne and Tony” and how she was never allowed to live with us or to have contact with us, and she often didn’t know where we were. Not being able to be a mother to Anthony and me caused her to be consumed with guilt which in turn deepened her depression.

Sometime after Doreen and Joseph had moved to Wellington to live, Doreen was admitted to Porirua Psychiatric Hospital for the first time, suffering from deep depression, on 25th February until the 2nd of April in 1947 according to Dr Taumoepeau …and this was when her bipolar disorder with psychotic episodes was first diagnosed. After that first admission, Doreen was re-admitted almost every two or three years (sometimes at her own request), usually for months at a time, and she received ECT on many occasions for severe depression. During her first admission, Doreen had wanted her son Kevin to stay with her Italian family in Wellington, but Joseph insisted that Kevin should stay with his own Lebanese family, although he had not yet officially adopted Kevin. Doreen’s psychiatrist also told me that Doreen had a very settled period in the late 1980s, up until about two years before her death.

I was always told by the Coory family that Kevin was illegitimate and that his father was an old man with a walking stick who lived further up Carroll Street. As I child I believed this to be true and Joseph never disputed these lies. In my teens, my cousin who is the same age as me, told me that our uncle Phillip, Joseph’s younger brother, was Kevin’s father and that he couldn’t marry Doreen because he was already married. In 1975, when Doreen came to Marlborough to visit me, I already knew the truth about who Kevin’s father was and that Joseph had adopted him before I was born.

Kevin told me that when they heard that Joseph was possibly dying from pneumonia and pleurisy in 1957, Doreen and Kevin flew to Dunedin, where Doreen dropped twelve-year-old Kevin off at 67 Carroll Street and then went on to find a hotel. I remembered that day because I was there visiting Joseph. There was a knock on the door, my uncle answered it and I saw there standing on the doorstep, Kevin, whom I hadn’t seen in years, carrying a suitcase. Two aunts were standing on either side of me and one of them asked what he was doing here. Kevin answered that he had come to see “my father” … my aunt told him that he couldn’t come in because he had made the choice to go and live with his mother… “but I don’t know where she is” Kevin replied. They told him in no uncertain terms that he couldn’t come in. I was scared and once again rooted to the spot, unable to move although my body ached to go and hug Kevin, who later described this to me as the most humiliating time of his life. He had to walk some distance to the police station and ask them to find his mother, and in the meantime the police found him a place to sleep at the YMCA while they searched all the hotels for Doreen. At that time, I had no idea where by brother Anthony was.

That image of Kevin standing at the threshold of the Coory family home carrying a suitcase, and which had caused me so much anguish at the time, has never left me. I have lost touch with Kevin over the last few years.

I was constantly indoctrinated by priests and nuns, both at St Dominic’s and at the Mercy orphanage, that I had to be pure, not to have impure thoughts and certainly not to have sex before marriage, and by implication, not to end up like my mother, so much so that my teenage years were utterly miserable. I was completely and utterly lost, going from one job to the next trying to avoid boys and men at all costs. So terrified was I of becoming like my mother, who of course at that time, I scarcely knew. However, after I met her in the Coory family’s backyard in Carroll Street, we re-connected and after that episode I began to search for her red hair whenever I walked around the streets of Dunedin.

During one of my visits to see Doreen and Kevin when I was a teenager, (which we had to keep secret from the Coory family, some of who lived in Wellington) they told me about the time they were struggling to survive while living in the state house at 56 Hewer Crescent, Naenae, in Lower Hutt, and Doreen was working at the Zip factory close by.

Q12. How old was your younger brother when he, in turn, came to the orphanage, and what year was that? What was his experience?

Anthony was about seven months old, and was first admitted to St Agnes’ Nursery on 13 May, 1950, which was managed by Sister Christopher who was very fond of Joseph due to his supposed devotion to Anthony and me. Sister Gregory was in charge of St Joseph’s Boys’ Home when Anthony lived there, and I interviewed her at the Catholic convent at 19 McAuley Crescent, Waikiwi, Invercargill in 1992. She remembered Anthony well, as I in turn remembered her from those days. At the time I interviewed her, she was elderly and very softly spoken, and also a little hesitant to say much. I got the impression from her that nuns were receiving a lot of harsh criticism for their treatment of children in Catholic homes in the past, but told me that they thought they were doing the right thing. I detected a fair amount of guilt in the way she said it. There is no doubt Anthony was a deeply traumatised little boy. Whenever Kevin and I have asked him about what he remembers of the past, he says he remembers nothing about his early childhood. He did not have a good formal education, but now has a steady career, and he kindly looked after Joseph until he was admitted to Cherry Farm, even though in the early days Joseph wanted to have nothing to do with Anthony because “…he is not my son”. Anthony also looked after Joseph’s dog Tim until he died. Anthony moved to Wellington permanently around the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Anne Frandi-Coory’s father Joseph Coory with his beloved dog, Tim.

Anthony also worked with Kevin in his high profile and successful restaurant, The Bacchus, in Wellington for a few years, and built a close adult relationship with Doreen, who also worked at the restaurant as a dishwasher.

I have only met up with Anthony occasionally over the years, because he is very close to the Coory family, whereas I am still terrified of them, so much so that when I am in their company, I can barely put a sentence together and then only with a voice I can barely muster. Kevin and I do have suspicions that Anthony was sexually abused during his childhood in Catholic institutions. He is gay and lives alone. You will have to contact Anthony for more complete answers to those questions concerning him. I do not know where he lives in Wellington.

As I have related above, Anthony could barely speak until he was five or six years old. He was severely beaten with a belt by uncle Phillip in my presence, but he says he doesn’t remember that either. That particular beating left him screaming and sobbing, which he ‘asked for’ because he and I had stolen two empty soft drink bottles to take to the dairy to cash in to buy lollies, while I was so terrified, I hid.

Q13. When were your brothers moved to the Doon St orphanage and why? What was their experience like there?

I do not have a memory of ever visiting Kevin at St Joseph’s Boys’ Home in Doon Street, although I do know he was living there for a very short time. Anthony was moved from St Agnes’ Nursery to the Doon Street Home when he was five years old in 1954 while Sister Gregory was in charge there. There was gender segregation when boys turned five, and siblings were separated regardless of the emotional damage it might cause. I interviewed Sister Gregory in Invercargill in 1992 and she remembers Anthony and me very well. As I have said above, Anthony has blocked out all memories of his time at the Doon Street orphanage, and I can only relate what I, Kevin and Doreen witnessed whenever we visited him there and when he lived with me at St Agnes Nursery.

Q14. What year were you finally able to leave, and how did this come about?

My father told me one day in 1955 at St Vincent’s Orphanage when I was about seven or eight years old that I would soon be going to school at St Dominic’s Boarding College in Rattray Street. I remember being very anxious when he told me this but I don’t recall him giving me a reason. When I met Sister Joanna at the disused orphanage in Macandrew Road in 1992, I asked her what the reason might have been for my father shifting me to St Dominic’s after all those years. She explained that at that time the Lebanese community was well settled in Dunedin and many Maronite priests were coming to Otago for further education. The Lebanese community were by then largely well off and were contributing some of their wealth to St Joseph’s Cathedral and the attached Dominican primary and secondary Catholic schools, and while most of their children attended those schools, I was the only Lebanese girl who was a boarder. I became a boarder at St Dominic’s around 1956.

Sister Joanna informed me that the Vatican had made changes to Canon Law, and there were other big changes afoot within the Catholic Church. Numbers of orphans and destitute families were dwindling, and there were fewer nuns and priests taking up those vocations.

Q15. What do you think motivated the treatment dished out by the nuns, and what do you think of their behaviour, and of the Catholic Church, now, looking back?

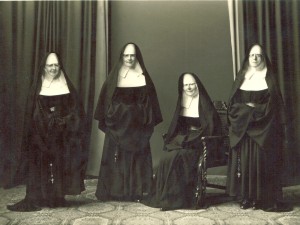

The habits worn by the Mercy nuns when Anne and her brothers were living in the Mercy orphanage

I believe that Catholic nuns and priests were unfit to have full charge of young children. While living in these Catholic total institutions, we were indoctrinated to the point that we could not think for ourselves, were terrorised daily about what awaited us in the fires of hell if we sinned. We were preached at daily, about how Jesus died on the cross because we were born with Original Sin …that we had to suffer here on earth to have any chance of getting into heaven. Graphic images of Christ hanging on a cross, with blood dripping down his side and out of his hands and feet, not to mention the blood on his head from the crown of thorns, were everywhere, to remind us daily what we had done to this poor man. Every nun had a large crucifix hanging around her waist.

These Catholic men and women (priests and nuns) had no idea how to educate and raise healthy and well-adjusted children, let alone children who were deeply traumatised.

Corporal punishment was barbaric, especially when it involved children who had done nothing more than talked in the hallways or at the table during meals when we were forbidden to talk other than to say grace, or some other minor ‘sin’. These men and women took it upon themselves to separate siblings from each other by gender when boys reached five years old, which added to the despair and anguish felt by children already suffering deep trauma.

From research I’ve done, and from knowing my own mother’s reasons for entering a convent, many nuns and priests took up their vocations because they were either indoctrinated themselves from childhood, wanted to escape violent home lives, or had some sort of anti-social disorders. Then there were the sexual perverts who believed that having control over so many children meant that they could do anything they wished to them and no-one would care because no-one wanted them, not even their own families.

The fact that the teaching nuns labelled traumatised children ‘backward’ or ‘feebleminded’ or ‘imbeciles’ was especially cruel. In Anthony’s case he was sent to a special school at St Bernadette’s because he couldn’t read or write when his peers were able to, and I can remember at St Dominic’s time and time again, when I excelled at some subject, I was queried as to whether it was all my work. I remember in one case in form one, in an art class we had to sketch a copy of a famous work of art, and when the teacher saw my effort, she asked if it was my own work, and when I said yes, she asked, “…are you sure?” I didn’t know how to cheat, even if I had wanted to!

On many occasions the nuns took their anger and spite out on us children… we were lost children but were seen as slaves to do their bidding, even when we were supposed to be learning in the classroom. They had total power over us and we could never escape their control 24 hours a day. All the nuns and priests cared about were our souls, they had to be white but if we committed sins, our souls would have black spots on them and god would not be happy.

I didn’t even know that I had a body from the neck down because as the nuns told us, our bodies could lead us to sin. The nuns always wore habits that covered their whole bodies except for their faces so we never saw a naked adult body and of course to look at another child’s body was a sin too.

Q16. What has been the lasting impact on your life, and the lives of your brothers, from all of this?

Anthony and I completely missed out on any form of normal socialisation during our formative years in Catholic institutions. There can be no doubt about that. It has taken me almost my entire lifetime to overcome the impact that spending all of my formative years in a Catholic institution has wrought upon me. Only now at age 70 years, can I truly say that I feel secure and safe. I have written two books, taught myself to paint, but not until I was in my sixties, and I only wish that I had begun to really live a full life so much earlier, because now I am running out of time, and going blind, because of the neglect and deprivation I experienced during my childhood years. Neither my brothers, or I, have ever reached our full potential.

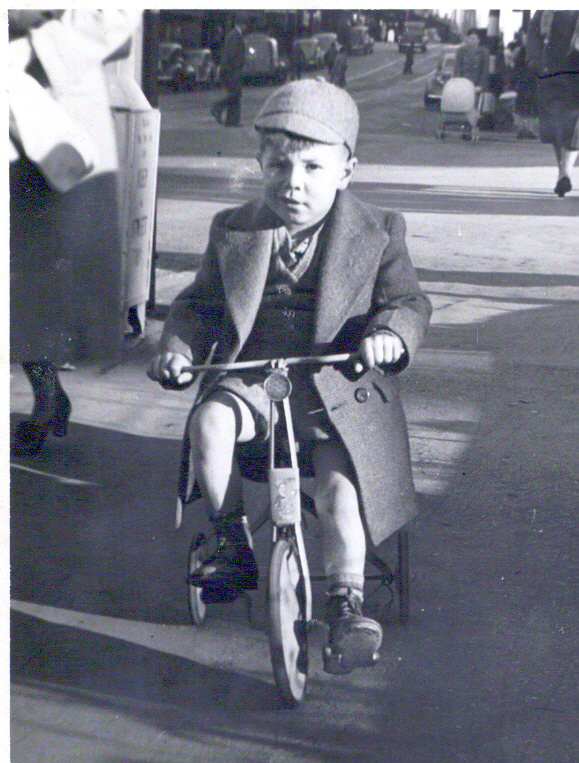

You would have to ask my brothers this question for a full answer, but what I do know is that Kevin had a dreadful life living with Doreen when he was a child, and that he never was able to visit Joseph, the only father he ever knew. I remember Joseph talking about Kevin all the time and for Kevin’s first five or so years he had a close relationship with Joseph. Photos certainly show a happy little boy and I do remember Joseph taking me to Carroll Street when Kevin lived there and he did seem happy, playing in his peddle car and laughing at the time. When Doreen decided eventually, after her divorce from Joseph, to return to Wellington where her extended family lived, Kevin wanted to go with his mother. The Coory family from that moment on refused to allow any contact between Kevin and Joseph.

Kevin

When they moved to Wellington, Kevin often stayed all night at movies which ran 24 hours if Doreen was in hospital and he also had to deal with her sexual liaisons with other men, and of course her mood swings. None-the-less he was always loyal and caring towards her, but it wasn’t the kind of life any young boy should have had to endure. Kevin has never been able to sustain a happy personal life with a woman, although he does have two children with whom he keeps in touch. Anthony has no children and from what I know, he lives a lonely life on his own, although he still has contact with some Coory family members.

My two brothers and I grew up living separate lives for the most part, and so have never really been siblings in the true sense of the word i.e. having the same reference groups, shared memories of a happy home life, or been able to offer support to each other. That sense of loss is always with me.

******************

More here about Anne Frandi-Coory’s memoir WHATEVER HAPPENED TO ISHTAR?